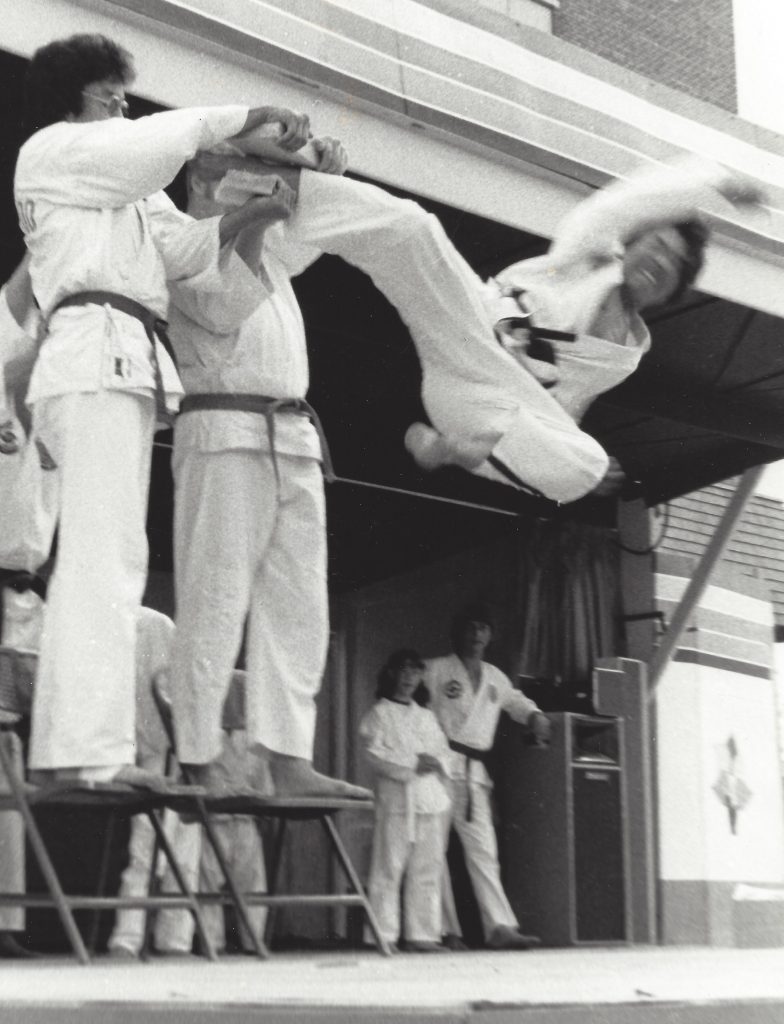

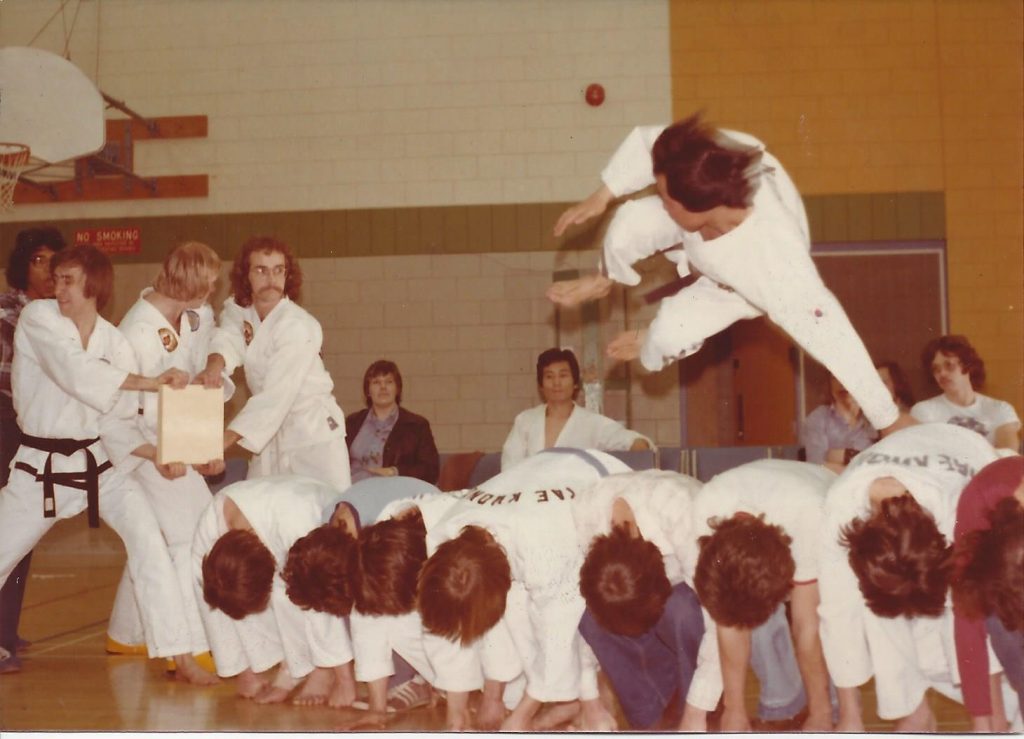

When I first began training in the martial arts, my instructor, Park Jung-Taek, disappeared. My guess is that he went to North Korea. I was training in Ottawa when he suddenly left in 1983. I liked and respected him, so it difficult to hear that he was gone. He was an astounding martial artist, as you’ll see in this video from 1993 and the photos below. I don’t need stories about fake Korean warriors (the Hwa-Rang) to know the power of the martial art in those days. I think of Muhammad Ali and Bruce Lee studying traditional TKD, and I think of champions such as Grandmaster Park Jung-Taek, who was a pioneer in helping to create the art.

But, for decades, I always wondered what happened to him. I’m hoping that some of you can help me with details. He didn’t use social media, until his son set up a Facebook page recently, and none of the Tae Kwon Do masters I interviewed over the years would talk to me about him.

Thanks to Jonathan Park, his son, I heard some of the stories about his father’s secretive political and athletic activities. GM Park demonstrated Tae Kwon Do in 60 countries, mainly helping Choi Hong-Hi’s International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF), but he also helped with Karate, especially Kyokoshin Karate. And he trained many North Koreans, even though it was rumoured he worked with the South Korea CIA. “There are photos of Park with Kim Il-Sung,” says Jon Park, referring to the former North Korean leader. “My father sympathized with him and spent quite a bit of time there.”

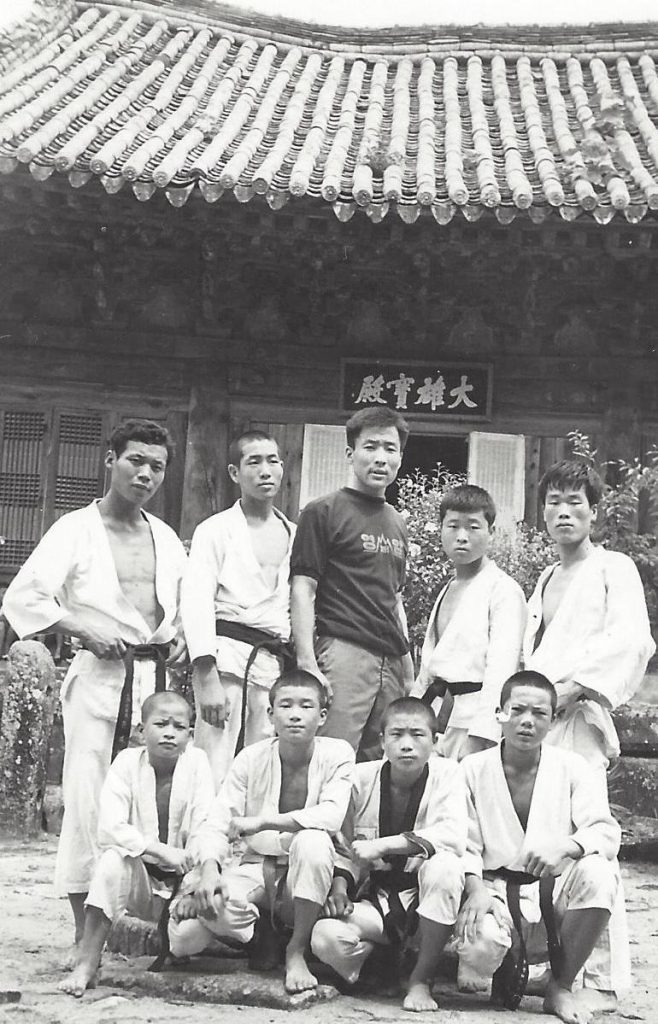

When I trained with GM Park in Ottawa, I didn’t know about all that. I only knew that he disappeared. I remember his big hands, which had flat knuckles from punching things, and I remember that he was fast and powerful – and that he married one of his students, Glenda. Park began training when he was eight years old, in 1956. As did so many other martial artists in the early years, he tried to survive the chaos in South Korea. “It was an outlaw country, because of the Korean War,” Jon Park explains. “His father put him in Tae Kwon Do to keep him out of trouble.”

In Canada, GM Park also taught Tae Kwon Do in Mississauga and Burlington (Ontario) and in Brandon and Winnipeg (Manitoba), as well as in North Carolina, USA, and in North Korea. He travelled extensively with Choi Hong-Hi, who, in the early 1980s, was busy avoiding the police because of his involvement with a botched plot to assassinate the South Korean president in 1980. Park helped Choi to work on the 15-volume Taekwon-Do encyclopedia. I remember that huge project, because, before Park disappeared, he and Choi recruited black belts from the Ottawa gym where I trained. I still recognize many of their photos in the encyclopedia.

Park also co-founded a non-profit organization in North Carolina that promoted reunification of North and South Korea, and he continued travelling to North Korea. It was an extremely dangerous undertaking, because in South Korea, even talking to a North Korean was a crime, punishable by death in some cases.

“My dad was a nationalist,” Jon Park says. “He wanted a unified Korea.” Unfortunately, in 1994, South Korean officials caught up with Park Jung-Taek’s co-founder, who was carrying a lot of cash at the North Korean border. “He got a call that this guy was in prison,” Jon Park explains. “He chucked a coffee cup across the room after the call.” Park Jung-Taek knew he was in deep trouble. “My dad had political information that the South Koreans wanted,” Jon Park explains.

Park Jung-Taek’s life suddenly became difficult. He knew about conflict; as he once told one of his black belts: “Real fight, dog fight.” People began following Park and his family in Canada, and someone bugged their house. Park found the bug only after scouring every room. Then, one day, he fled.

“He disappeared off the face of the Earth,” Jon Park says. Only later did his friends and family learn that he’d gone into hiding at a safe house in the U.S. When he eventually returned to Toronto, he didn’t explain what had happened, and he never got involved in Tae Kwon Do again, not even to teach, partly because of a conflict with Choi Hong-Hi. (As I said, I don’t know the whole story.)

In May, 2018, Park Jung-Taek turned 70 years old. He has an ailment that’s deteriorating his mind and body, so he can’t remember much. His son organized a birthday party for him in Toronto, Canada, posting a few photos on his Facebook page. The party turned into a reunion. I couldn’t attend, but I’m glad his friends and family gathered around him. I can still picture him jumping over eight people to demonstrate a flying side-kick – and, during class, berating me, because I couldn’t even straighten my leg for my own side-kick. I kept at it for 35 years however, and it was his instruction that kickstarted my passion for martial arts history and techniques. Thank you, Grandmaster Park.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.