We often hear about North Korea and other dictatorships using Tae Kwon Do for espionage and political missions, but South Korea and the United States have a history of doing the same. During the first of three videotaped interviews in 2011, I asked Nam Tae-Hi, a martial artist who helped to create Tae Kwon Do in the 1950s, if he’d ever been involved with the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA). The audio is fuzzy, because the interview took place during a tournament, but he nodded yes.

It was an extraordinary admission from someone famous for helping to found a martial art based on Integrity, Courtesy and other tenets. The KCIA was known in his day for terrorizing people. Today, almost no one knows that Nam was a KCIA agent.

“What years?” I ask him in this video clip from my 2011 interview (with his son, Chris Nam, translating for us).

“1965 to 1972,” Nam replies.

“What was your role?” I ask.

“It’s confidential,” he says.

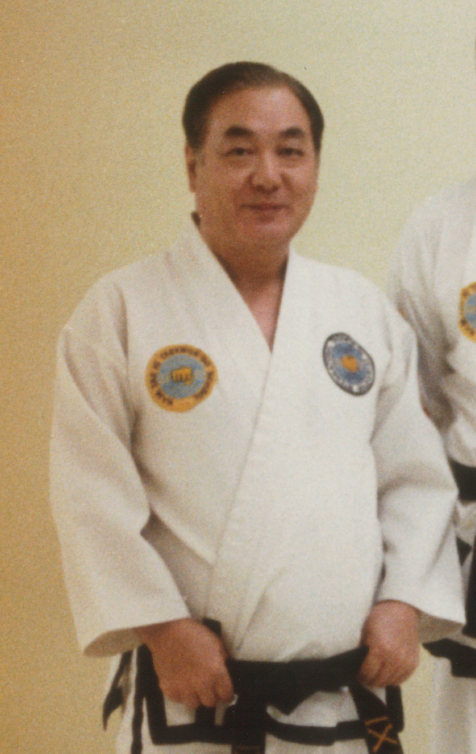

I knew this part of the interview would be difficult. I knew that few people had asked Nam about those years. Before he died in 2013, he was a grandmaster of Tae Kwon Do and one of my heroes. He still is my hero. In my updated book, “A Killing Art: The Untold History of Tae Kwon Do” (2016), I devoted a chapter, called “SuperNam,” to describing his incredible, three-day battle scene in 1951 and his now-famous demonstration in front of South Korea’s military leaders in 1954, when he smashed thirteen roof tiles with a single punch. But how do you reconcile your superhero with an agency that tortured and killed innocent people?

He and his brother-in-law worked for the KCIA in Malaysia from 1965 to 1970. I wanted to know what they did there. In the video, Nam turns to his son and asks: “Why does he want to know?”

“I’m wondering if Tae Kwon Do was involved,” I ask.

“There was no relation to Tae Kwon Do,” Nam replies. “My main role in Malaysia was working with the KCIA, but I continued to teach Tae Kwon Do there.”

“I ask because many officers, many soldiers, many Tae Kwon Do executives were also KCIA agents,” I say.

“I agree,” Nam says.

In the video, as well as in the second and third videos, I add that the KCIA and South Korean dictatorship channeled money to a bunch of American Karate and TKD gyms, such as Jhoon Rhee’s school, in the 1960s and 1970s. In my book, I also describe how the KCIA hired martial artists to do their dirty work.

“Although I don’t know exactly what happened, it would have been much easier to work with the KCIA if you also taught Tae Kwon Do, so there might have been a connection,” Nam says.

Jhoon Rhee and Nam weren’t the only ones with those connections. After Malaysia, from 1970 to 1972, Nam travelled, off and on, around the world with Choi Hong-Hi, the man who’d named Tae Kwon Do in 1955 and founded the International Taekwon-Do Federation in 1966. During those years, Choi feared for his life because of the KCIA, even though Choi had recruited high-ranking KCIA officials to become ITF executives. Nam, Choi and their super-athletes had turned Tae Kwon Do into one of the world’s the hottest martial arts, and some of these men collaborated in political and espionage activities.

Nam had respect for the KCIA, but he disagreed with its nefarious plans, especially one called “Koreagate” in the U.S. from 1970 to 1976, when KCIA operatives and their martial-artist thugs threatened Korean-Americans and bribed American politicians. Martial artists worked for the KCIA branches in charge of assassinations, abductions, sabotage, and spy networks in Korea and overseas – and the KCIA and South Korean regime had helped to set up martial arts gyms in the U.S. and other countries to assist with those networks. For example, between 1970 and 1976, the KCIA hired martial artists in Chicago, Washington, New York City, San Francisco and Los Angeles to harass, interrogate or kidnap people who criticized the South Korean regime. Nam lived in Chicago at the time, in the middle of the whole thing, but he says that he wasn’t involved — and that the KCIA didn’t fund his gym.

“It costs a lot to open a dojang (a Tae Kwon Do studio), and I’m guessing they might have been funded by the KCIA, but I was not one of them,” Nam says. And in this second video clip, he explains more. As noted by George Vitale, a martial arts leader and writer who was holding the camera during my interview with Nam, the KCIA wasn’t only nefarious; it also promoted TKD simply as a cultural and athletic activity.

I’m glad I asked Nam about his role. Choi had accused him of a few things – like accepting money from the KCIA – and Nam needed to tell his side of the story. My long interview with Nam clarified that that the KCIA had no role in his Tae Kwon Do. In fact, he was often caught in the crossfire between Choi and KCIA agents spying on Choi. For example, in this third video, Nam tells me that during a 1970 world tour, the South Korean embassy in each country would host dinners or social events for Nam, Choi and the athletes.

“There was always at least one KCIA member present,” Nam says. “At these dinner parties, which included ambassadors, councillors and high-ranking representatives of Korea, General Choi badmouthed South Korean President Park Chung-hee.” Choi had been angry at Park and other generals for excluding him from the May 16, 1961, coup d’etat in South Korea, and Choi had always looked down on Park in any case. Nam said that KCIA agents would routinely report Choi’s trash-talk to Park, including the badmouthing during the 1970 tour. This was terrifying, as Park had a reputation for killing his enemies.

“General Choi must have felt unsafe in Korea,” says Nam of Choi’s time after the 1970 tour.

In 1972, Choi fled to Canada, with Nam at his side. Nam left the KCIA that same year, he says. As I describe in my book, Nam moved to Chicago, Illinois, and opened his own gym – and started a new life as an American.

During my interview with him, Nam got emotional when telling me these final stories. He seemed near tears in parts of the video, but he told his stories anyway. I admired his courage in more ways than one. He was SuperNam.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.